The Life of a Showgirl: When Taylor Swift Lost the Plot

By Isabelle Redfield

There was a time when Taylor Swift was the soundtrack of our young female lives. “Enchanted.” “Hey Stephen.” “Our Song.” The music video to “You Belong With Me.” These were some of the first songs that ever made me want to write something down.

It was small-town, romantic, and unvarnished. The Taylor Swift I loved was that innocent girl standing under the porch light. She sang like someone who still believed that love didn’t have to be a power struggle or a villain origin story.

That girl is gone.

And maybe that’s the point. But I keep thinking about the distance between Fearless and Life of a Showgirl— between “maybe I was naïve” and the brash declarations of conquest that spill from her newest album like champagne at a party no one really wants to be at. Because Swift tips her hat to marriage and family in her newest album, feminists are in an uproar. But these milestones mean nothing if they don’t come with maturity and its fruits: poise, grace, forgiveness, and self-assuredness. Fear not, feminists, The Life of a Showgirl has none of that.

Eight of the twelve tracks are explicit— not just in language, but in posture. Gone is the wry diarist of the high school cafeteria; in her place is a woman insisting on her own vulgarity, as if daring us to look away.

We can’t. Taylor Swift has become too big to ignore, a global economy unto herself. The outfits, the boyfriends, the stadiums— each era a new act of self-reinvention. But somewhere in the spectacle, something precious was lost. Life of a Showgirl feels less like an evolution and more like a capitulation: to the algorithm, to the roar of the crowd, to the notion that a woman’s worth must now be measured by how brazenly she smashes her mystique.

There’s a line in “Wood” that made me stop the song altogether. I won’t repeat it here— there’s no need— but it carries the dull thud of a door slamming on girlhood. It was vulgar not because of the raunchy innuendo itself, but because of the vacantness behind it. This was not rebellion or artistic experimentation— it was exhaustion dressed up as power.

And then there’s “Elizabeth Taylor,” a song meant to be clever and empowering. It isn’t. It’s hollow. It’s corrupt. What it exposes— perhaps accidentally— is Taylor’s weariness. A longing to be both adored and unbothered. The need to prove that nothing touches her anymore.

And yet, for so many of us, her vulnerability and the way she protected her virtue were her original appeal. Even as recently as 2020, “Invisible String” was a sweet reflection on how stars align to bring two people together. What girl, friend, sister hasn’t sung “Forever and Always,” windows down, hair flying, feeling free to feel deeply and unironically?

“‘Cause it rains in your bedroom - Everything is wrong - It rains when you’re here and it rains when you’re gone,” she sang, “‘Cause I was there when you said, ‘Forever and always.’”

For millions of women, the song still captures the sting of an unexpected breakup. While Swift, now weathered and supposedly wiser, may think she’s outgrown such a sentiment, many of her fans still find solace in it.

We can pretend Swift’s latest work represents “artistic growth.” But we should also be honest: what our girls listen to matters— what we listen to matters.

The words they memorize, the women they emulate, and the cultural ideas they internalize will shape them for years to come. And somewhere along the way, Taylor Swift stopped being an artist we could trust with our daughters, mentees, and even ourselves.

But there are musicians filling the gap for young women who want something intimate yet uplifting.

Enter Olivia Dean— British, twenty-something, and blessed with a voice that’s both effortless and carefully lived in, like a record you inherited from your mother but somehow already know by heart. Her songs— “Nice to Each Other,” “Cross My Mind,” “Lady Lady”— are about falling in love, yes, but also about finding herself. There’s no bitterness in her tone, no pose of irony. Just warmth, approachability, and soul.

She could become the big sister that Taylor Swift has long ceased to be for young women.

Dean teaches that womanhood is an art. Indeed, as her album is named, The Art of Loving. Sometimes it’s messy, but it’s always beautiful. It’s learning, forgiving, and dancing your way out of heartbreak without needing to humiliate anyone in the process. In the bouncy and spirited “Ok Love You Bye,” she maturely recognizes that relationships require looking in the mirror and showing your partner their own mirror— and reconciling when all is said and done.

Watching her live is watching joy incarnate. She is stylish without being performative, elegant without pretense.

I suppose that’s what I miss most— the idea that women can wear elegance proudly. That a woman could be respected without being coarse. That a song could be real without being indecent.

Olivia Dean reminds me that music once sounded like that. Her work feels like a return to civility, to musicianship, to sincerity. She sings as if she knows the difference between being adored and being admired— and prefers the latter.

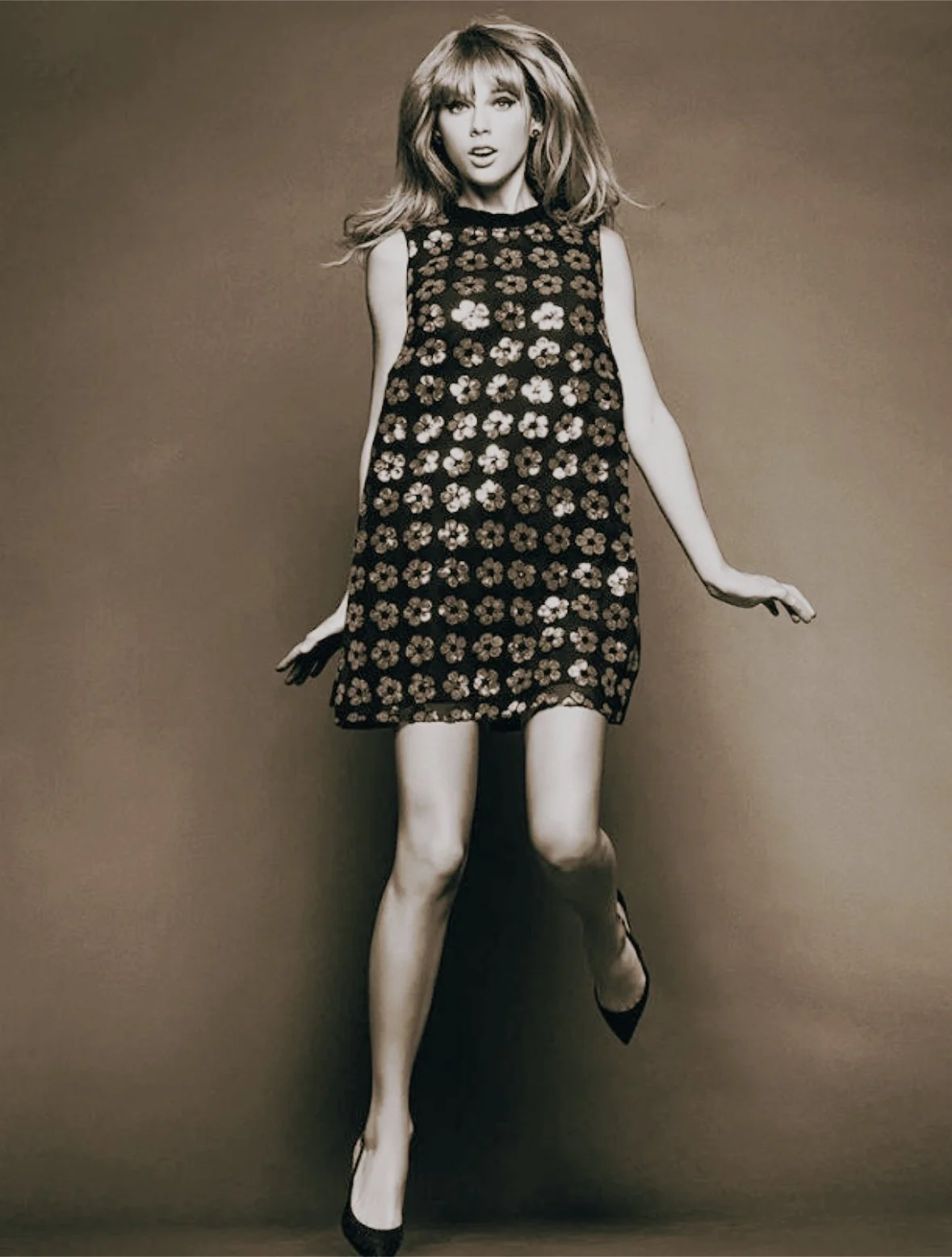

I don’t want to indict Taylor Swift. I don’t even want to scold her. I want to mourn her. Life of a Showgirl was her final goodbye. Because once, she was ours— the girl next door who turned heartbreak into poetry and didn’t try too hard to stick it to anyone. And now she’s another burned showgirl in sequins, her talent buried beneath layers of artifice and profanity, her voice still beautiful but somehow unrecognizable.

We were promised that growing up would mean more wisdom, more self-possession. But somewhere between Fearless and The Life of a Showgirl, it started to mean less restraint, less thoughtfulness, less care.

So yes, I’ll still hum “Our Song” when it finds me. But when I want to feel the wonder of womanhood, I’ll turn to Olivia Dean. I’ll let her remind me that it’s still possible to be modern without being jaded, strong without being loud, feminine without apology.

Because the best music doesn’t just play in the background of our lives. It tunes us back to grace.

Isabelle Redfield founded The Conservateur while studying at Southern Methodist University. Her previous experience includes roles with the United States Senate, Fox News, the Republican National Commitee, the Trump Campaign, and the White House. She now lives in Washington, DC. Find her online @isabelleredfield